New Boss, Same Plantation: Joseph Walters and the Grievance Machine

Deputy Director Joseph W. Walters was elevated to lead the Virginia Department of Corrections. His portfolio has long sat where prison labor, “compliance,” and the grievance maze intersect.

When Governor Abigail Spanberger moved to replace Chadwick Dotson at the Virginia Department of Corrections, the public hoped for change: a break from the violence, retaliation, and secrecy that have defined Virginia’s Western Region prisons. The man elevated to run the system, Deputy Director Joseph W. Walters, was presented as a steady technocrat.

Look at the record, and a different picture emerges. Walters is not an outsider brought in to clean house. He is the longtime administrator of the plantation economy inside VADOC: the official who sits over money, labor, “compliance,” HR, and the very grievance maze that keeps people out of court.

Across at least 29 federal civil cases naming him as a defendant, Walters appears not as a reformer but as a constant: the signature at the top of a regime that survives by controlling both the bodies and the paperwork.

The man over the maze

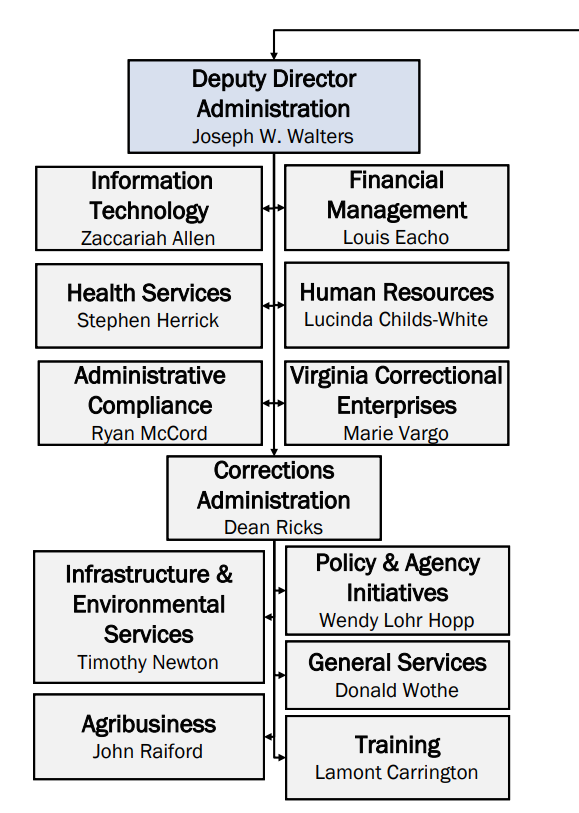

The org chart makes Walters’ role plain. As Deputy Director for Administration, his name sits at the top of a column that runs through Information Technology, Financial Management, Health Services, Human Resources, Administrative Compliance, Virginia Correctional Enterprises, Corrections Administration, Infrastructure and Environmental Services, Agribusiness, Policy and Agency Initiatives, General Services, and Training. These are the offices whose outputs—policies, trainings, compliance certifications, medical practices, hiring and discipline decisions, procurement and facility records, and grievance metrics—are later treated by courts and auditors as neutral evidence of constitutional adequacy.

This is not a side wing of the agency. It is the core of how the regime reproduces itself on paper: who gets hired and promoted, what happens when staff are accused of abuse, how medical neglect is documented or blurred into “non-compliance,” how force reports and grievances are coded, how prison labor and contracts are justified, how auditors are walked through “compliance” checklists. Wardens and line staff may deliver the blows, but Walters’ division designs and maintains the administrative environment that makes those blows disappear into procedure.

Administrative Compliance, which sits under his supervision, is also where grievance rules and many of the operating procedures live. That is the level at which VADOC decides what counts as a “proper” informal, how many hoops a person must jump through, what deadlines apply, what counts as a disqualifying technical error, and how facilities are scored for “compliance” with those rules. Walters may not be the one rejecting individual forms, but the rulebook, the training, and the internal audits that courts later rely on all run through his side of the house.

A colonial economy in bureaucratic dress

Virginia has built an internal colony in its own southwest corner. People from Black and poor communities in Richmond, Tidewater, and Northern Virginia are pulled hundreds of miles into a prison belt in Wise, Buchanan, and Russell counties, stripped of any real political voice, and folded into an economy built around cages. It is a new layer on an old pattern: a state that once ran on enslaved labor and, later, on chain gangs and company coal towns now staffs rural prisons to keep that coercive labor structure alive under another name. In county after county, the same surnames that show up in nineteenth-century slave schedules and land records show up again in the rosters of sheriffs, judges, and corrections officers; families whose names appeared as slaveholders now occupy offices that control confinement.

Inside that belt, prisons function as anchor employers. Entire counties are effectively put on a payroll to guard and break people from the rest of the state: corrections jobs, medical contracts, food and construction vendors, agribusiness, Virginia Correctional Enterprises shops. Walters’ side of the house—financial management, VCE, agribusiness, HR, administrative compliance—sits where all of that is coordinated: the budgets and contracts, the staffing pipelines, the policies that decide who is shipped out of Richmond or Norfolk and who is put to work on which line. His division does not just manage a bureaucracy; it manages the extraction circuit.

That is what makes the Western Region an internal colony rather than just a “poor region” or “periphery.” Wealth and political advantage flow outward, while risk and trauma are concentrated there. Local white-majority workforces are paid to police overwhelmingly Black and brown prisoners from the cities; state funding and federal dollars follow the headcount; and the same offices that profit from the labor also control the paperwork that defines what that labor “is.” Walters sits where the labor system, its staffing, and its paper shield meet, making the plantation economy read as ordinary administration.

Twenty-nine cases and a pattern of impunity

Against that backdrop, Walters’ litigation footprint comes into focus. There are 29 federal cases in Virginia where he appears as a defendant. In most of these cases, Walters is named not for direct acts, but as the senior policy official responsible for the administrative systems being challenged.

Eastern District cases like Webb, Meyers, Perkins, Tyler, and Monzon raise conditions, medical neglect, retaliation, and grievance obstruction tied to policies that flow through Richmond. Western District cases like Mangus, Watson, Barksdale, Reid, Lumumba, Deans, and Chenevert are rooted in the brutal daily reality of Red Onion, Wallens Ridge, and their satellite camps. Routon and related medical-provider suits recur with Walters in the leadership tier that contracted, oversaw, and then defended third-party “correctional health” vendors as abuse and neglect accumulated.

In case after case, Walters is not the counselor or the guard. He is the policy-level defendant, the man whose name stands in for “the people who built this system and refuse to change it.” And in case after case, the claims fail at the threshold—dismissed before factual development, often on exhaustion or immunity grounds. The underlying pattern of labor exploitation, retaliation, and medical neglect remains intact.

Those 29 Walters cases are not happening in a vacuum. During the same 2021–2024 period, Virginia quietly paid out more than $5 million in publicly documented § 1983 settlements and verdicts tied to its prisons: a $1.875 million payment in Boley after a jury found wrongful death from an untreated aneurysm, $1.6 million in Puryear for over-detention, $700,000 in Pfaller for a hepatitis C death, and additional six-figure settlements in Reyes, Lee, NFB-VA, and the Duynes estate. Walters is not named on every caption, but every one of these losses comes out of the same administrative and medical systems he helped oversee. When plaintiffs manage to break through the grievance maze and the PLRA’s procedural traps, the pattern is blunt: the state pays. What changes is not the system, but the titles of the people who keep it running.

Walters’ institutional leverage: the PLRA and the grievance contradiction

This is where the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) meets Walters’ portfolio. As Deputy Director for Administration, Walters sits over the units that write, “audit,” and defend VADOC’s internal rules—Administrative Compliance, HR, Corrections Administration, Training. Under federal law, people in Virginia’s prisons don’t have any constitutional right to a fair or even functioning grievance system. But under the PLRA, they are barred from federal court unless they navigate every step of whatever grievance maze VADOC chooses to design. That contradiction is a key source of Walters’ institutional leverage.

This system does not require overt conspiracy to function—only the routine maintenance of procedures that courts are trained to defer to. His shop builds the maze, trains staff to run it, declares it “in compliance,” and then watches courts treat that paper system as proof that remedies were “available” when prisoners’ cases get thrown out on exhaustion.

UPROAR has received and shared reports from the Western Region that make “availability” a dark joke. In some pods, the grievance box itself sits behind a painted red line. UPROAR has documented accounts alleging that access to grievance boxes is enforced through threats of force, including reports of less-lethal munitions used to deter approach. On paper, the grievance process remains pristine and “available.” On the ground, it is guarded by threat of physical punishment.

The 29-case docket against Walters lives inside this contradiction. Plaintiffs allege beatings, retaliation, denial of medical care, sexual harassment, grotesque conditions. The cases are met not with real accountability, but with threshold defenses: “failure to exhaust,” “no personal involvement,” “no clearly established right,” “official immunity.” The same system that makes people risk rubber bullets to reach a grievance box is then treated as if it worked flawlessly when courts decide whether they had “available remedies.”

Walters’ role over Administrative Compliance makes him the custodian of this legal fiction. If the grievance maze were redesigned to be simple, safe, and accountable, that would threaten the very mechanism that currently keeps most suits from ever reaching a jury.

Oversight over its own overseers

The OSIG Red Onion report shows how this plays out at scale. After years of reports about beatings, starvation, racist retaliation, and desperate acts of self-harm at Red Onion, the Virginia Office of the State Inspector General issued an investigation report on “conditions of confinement.” VADOC leadership immediately began citing the report as vindication—proof, they claimed, that allegations were “unsubstantiated.”

UPROAR’s public analysis of that report walks through the reality: OSIG relied heavily on VADOC’s own records, accepted the department’s grievance and incident tracking at face value, and treated a long trail of brutality and self-immolation as administratively invisible whenever the paperwork didn’t line up. Where people were too scared to grieve, or where grievances were blocked, delayed, or destroyed, OSIG simply found “no evidence.” That procedural absence was then used as a political shield.

That shield is forged in Walters’ world. Administrative Compliance decides how use-of-force, medical neglect, and retaliation are supposed to be recorded. HR and leadership decide who gets disciplined, who gets promoted, and who keeps running a housing unit after repeated allegations. When outside investigators or courts come knocking, the only “facts” they see first are the ones produced by that system. The reliability of those records traces directly back to the administrative offices Walters oversaw for years.

The result is oversight over its own overseers: the same regime that abuses, starves, and buries people in segregation also supplies the “evidence” that supposedly clears itself. Walters’ career sits right at that junction.

Spanberger’s choice: continuity, not rupture

Chadwick Dotson’s tenure as VADOC Director brought the Western Region’s brutality into sharper public view, but he did not invent it. The abuses documented by prisoners, families, and advocates long predate him. They are the product of a structural arrangement: a carceral plantation economy run through an internal colony in Southwest Virginia, insulated by a grievance and oversight apparatus designed to fail the people it claims to protect.

By elevating Joseph Walters—the overseer of that apparatus—to the top job, Governor Spanberger did not break with that regime. She promoted it. The man whose division manages prison labor and agribusiness now presides over the entire system that profits from that coerced work, and the official whose chain of command runs through Administrative Compliance and HR now has the final word on how VADOC responds to OSIG findings, FOIA pressure, and civil-rights litigation. The defendant in at least 29 federal cases alleging harms under his watch is now the public face of “reform.”

“New boss, same as the old boss” is not a slogan here. It is a description of institutional continuity. Walters’ rise shows that the thing the regime values most is not safety, not accountability, not the lives of the people trapped inside its walls, but the continued smooth operation of a system in which grievances are dangerous or pointless, oversight depends on DOC’s own paperwork, and those who help maintain that impunity are rewarded with promotion.

Virginians who are serious about ending the plantation economy inside their prisons cannot treat Walters’ appointment, or Governor Spanberger’s role in promoting him, as a misunderstanding to be politely corrected. They have to understand it for what it is: a deliberate consolidation of the apparatus that now governs Virginia’s prison crisis. That apparatus takes an internationally reported pattern of racist abuse—punctuated by self-immolations, unexplained deaths in custody, and increasing attacks on guards—and turns it into a “mostly unsubstantiated” administrative mystery.

To confront that system, Virginians must treat Walters and the administration that elevated him not as partners in reform, but as managers of an entrenched regime that chooses impunity over human life. The task then is to learn more, fight harder, and organize on a different scale: to build real inside–outside unity between imprisoned people, their families, and supporters on the street, and to knit together unions, grassroots groups, faith communities, and abolitionist formations into a common front. That kind of unity—across the walls and across movements—is what it will take to break the information monopoly that keeps abuse “unsubstantiated,” to force an end to the most dangerous practices, and to make it politically impossible to keep calling consolidation “reform.”

Leave a Reply