The New Prison Movement: The Continuing Struggle to Abolish Slavery in Amerika (2018)

The rising new prison movement

Across Amerika (home of the world’s largest prison population) growing numbers of the imprisoned are coming to realize that they are victims of social injustice.

Foremost, they are victims of an inherently predatory and dysfunctional capitalist-imperialist system, which targets the poor and people of color for intensified policing, militaristic containment, and selective criminal prosecutions while denying them access to the basic resources, employment and institutional control needed for social and economic security. Deprivations, which generate “crime”—economic crimes, crimes of passion, and crimes of attempting to cope (through drug use and addictions.)

Secondly, once imprisoned they become victims of inhumane abuses, warehousing, and one of the most decadent and dehumanizing forms of social economic injustice—slavery.

This rising awareness among the imprisoned has prompted increasing numbers of prisoners to unite in resistance proclaiming “no more!” And the momentum is building.

This “new” prison movement is seeing growing waves of open resistance to slave labor and conditions of abuse, which is eroding the structures put in place beginning nearly 50 years ago to repress the prison movement of that era, such as solitary confinement.

From yesterday’s suppressed prison movement

During the earlier wave of the prison movement (of the 1960s-70s), when the courts barred their doors against prisoners’ lawsuits seeking redress against the inhumane conditions that pervade U.S. prisons, the prisoners rose up in resistance.

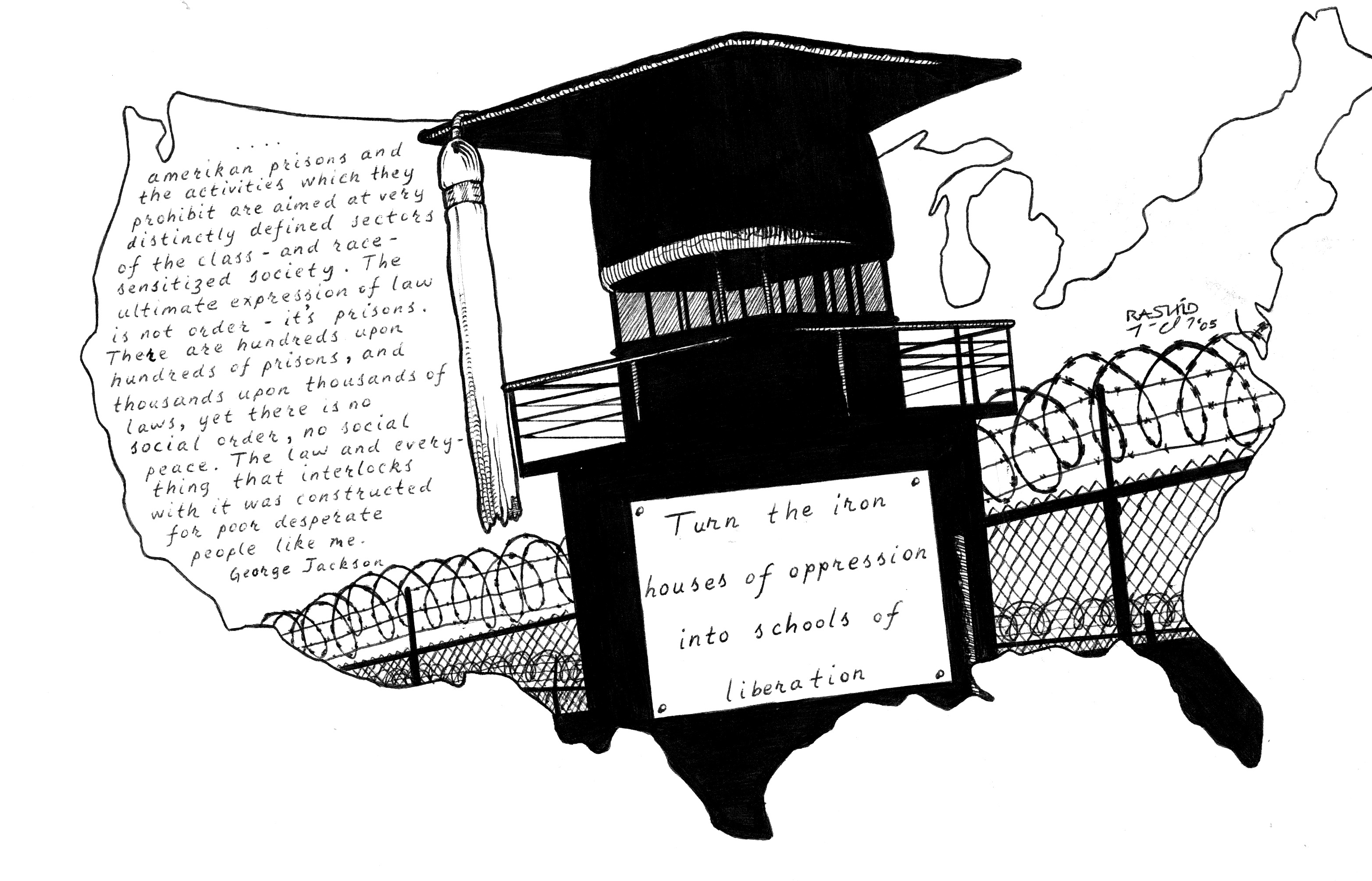

In a dialectical relationship, their movement both informed and was informed by revolutionary ideas then prevalent in the broader social movements of the time, which exposed and challenged the capitalist system. At the forefront of that movement was the original Black Panther Party and allied groups on the outside and comrades like George Jackson who formed the BPP’s first prison chapter on the inside.

To suppress that movement and stamp out its revolutionary consciousness, the establishment began constructing and operating solitary confinement prisons and units (called Supermaxes and Control Units) at an unprecedented level. Beginning with the Marion Control Unit which opened in 1972, after the assassination of George Jackson by guards, and the peaceful 1971 uprising at Attica State Prison that officials suppressed by murdering 29 prisoners and ten civilians, then tortured hundreds more, international outrage was sparked and the inhumane conditions in U.S. prisons was exposed.

In a rare admission of the actual political purpose of subsequent high security units, Ralph Arons, a former warden at Marion, testified in federal court: “The purpose of the Marion Control Unit is to control revolutionary attitudes in prison and society at large.”[1]

Alongside this repression also came concessions to the Prison Movement, including prison officials granting prisoners more privileges and the federal courts opening their doors to prisoner litigation challenging their living conditions. But this did not last.

As the U.S. prison system expanded eight-fold and solitary confinement units contained prisoner resistance the concessions were rolled back and the courts soon made rulings like Turner v. Safley,[2] and laws like the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA)[3] were enacted, that in effect reinstated the courts’ old “hands off” doctrine towards prisoner lawsuits.

Oppression breeds renewed resistance

With these reversals, abuse conditions intensified, especially with the vastly expanded use of solitary confinement, a condition which the U.S. Supreme Court found to be cruel and unusual and constituted torture back in the late 1800s,[4] and the attendant enlargement of prison labor pools to be exploited as free workers. Under these conditions of heightened abuse and exploitation a new prison movement has emerged and is only growing.

At each stage of this new movement record numbers of prisoners have joined and forged unity across racial and tribal lines by which the system has traditionally been able to keep prisoners divided and controlled. Even more monumental is that unity in these struggles has been achieved not just within individual prisons, but across entire prison systems and now across the country, with public support spanning the country and reaching international levels.

This has and can only inspire greater levels of resistance and help us refine our forms of resistance and methods of organizing and communication.

To these ends I’d like to summarize the major events in today’s growing waves of prison resistance and call on readers to join and support the struggles to come.

And resist we have!

When in 2008 a migrant, Jesus Manuel Galindo, was left to die in a solitary confinement cell from untreated epilepsy, hundreds of detainees at Reeves County Detention Complex in Pesos, Texas took over the complex and put it to the torch. Over $2 million in damage was reported in an uprising that united detainees from Cuba, Nigeria, Venezuela, and Mexico.

During December 2010, prisoners in six Georgia prisons went on a mass strike, protesting unpaid slave labor, solitary confinement, and other oppressive conditions. Latinos, Blacks, whites, prison tribes of all orientations, Muslims, etc., united in this protest. Following the weeklong strike, two years later at Jackson State Prison, where many of the 2010 strike leaders had been transferred, a 44-day hunger strike was staged as guards violently retaliated.

In 2011 and 2013 three historic mass hunger strikes were undertaken by California prisoners protesting indefinite solitary confinement and other abuses, where 6,000, 12,000, and 30,000 prisoners respectively participated. Prisoners in other states also joined the strike—in Virginia, Oregon, Washington state, etc. This strike united and was led by Blacks, Latinos, and whites, and all the major California prison tribes. Which led to a call by the prisoners to end all racial and group hostilities, and which Cali prison officials have repeatedly tried to sabotage. This strike and unprecedented unity alongside legal challenges by some strike leaders and participants forced the Cali prison system to reform its long-term solitary confinement policies and release some 2,000 prisoners to general population in 2015.[5]

Inspired by the 2010 Georgia prison strike, in 2013, prisoner leaders of the Free Alabama Movement (FAM) called for a strike in protest of Alabama’s “running a slave empire” and “incarcerating people for free labor.” In January 2014, prisoners at four Alabama prisons took up the strike. As a result of FAM’s organizing efforts and collaborating with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a committee within the IWW was formed called the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), which now has over 800 imprisoned members in 46 states. The IWOC has since played an important support role in subsequent strikes and building public support. Shortly after the IWOC’s founding, the IWOC and the New Afrikan Black Panther Party-Prison Chapter united as allies in this work, and I as a co-founder of the NABPP and numerous other NABPP members joined IWOC.[6]

In 2014, all 1200 detainees at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, went on a 56-day hunger strike, which spread to the Joe Corley Detention Center in Conroe, Texas, all protesting oppressive conditions at the facilities. Outside protesters organized in support of the strikers.

In April 2016, prisoners in seven Texas prisons went on a work strike at the call of leading comrades of the NABPP’s Texas branch and IWOC. The month before, a spontaneous uprising took place in Alabama at Holman prison, where the new warden, Carter Davenport, known for his role in physical assaults on prisoners, ended up on the receiving end of violence.

These initiatives in early 2016 inspired a call to prisoners across the U.S. to engage in a country-wide strike beginning on September 9, 2016, a date chosen to commemorate the 1971 Attica uprising.

September 9th proved historical as over 30,000 prisoners in up to 46 facilities in 24 states took up various forms of protest from refusing to work, to hunger strikes, to prison takeovers, to disrupting operations. Outside protests took place in various cities across the U.S. in support of the prisoners.

In response to the rising voices of prisoners resisting slave labor and abusive treatment, on August 19, 2017, a March on Washington was undertaken in support of prisoners and against the 13th Amendment which, enacted at the end of the Civil War in 1865, legalized enslavement of the criminally convicted, in violation of international law written and ratified by the U.S. after World War II, which forbids all forms of slavery and involuntary servitude.[7]

Shaken by the protests of September 2016, in an unprecedented move, states like Florida locked down their entire prison system hoping to head off any possible uprisings attending the August 19, 2017, Washington march. Florida went even further to serve its prisoners special gourmet meals during the entire four-day lockdown (from August 18-21).

Despite this move, Florida prisoners made an end run around officials and still undertook a strike code-named Operation PUSH, beginning January 15, 2018, on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. PUSH involved prisoners across the state refusing to turn out for work and boycotting the prison commissary. They were protesting unpaid slave labor, price-gouging in the system’s commissary and packaging services, the gain-time scam that replaced parole, compounded by extreme overcrowding caused by extreme sentencing, causing inhumane conditions.

As Florida prison officials scrambled to replace men who refused to work with more compliant ones and transferred and carted off strike participants to solitary confinement, they falsely reported to the media that no strike and no retribution against participants occurred—an outright lie.

As one of Operation PUSH’s main outside supporters informed me in a letter in late January 2018:

“I am receiving mail daily from prisoners all over Florids who are either participating in PUSH or being retaliated against for having literature or correspondence with outside organizations that support the strike, such as IWOC and FTP. Some have been outright threatened with punishments if they continue to talk to us…There was only six weeks of planning and it was covered by 50 news outlets including Newsweek, The Nation, Teen Vogue! I think we’re off to a good start and the DOC is lying that no one is participating.”

Not only this but I can bear witness to Florida officials’ lying about there being no strike, nor reprisals, because I also participated.

On the eve of the strike the warden at Florida State Prison (FSP) had me and nearly a dozen others with whom I was known to socialize split up, which we’d anticipated. This did nothing to prevent our planned boycott of the commissary for several weeks. In fact it allowed us to spread the word.

Then on January 10th the warden had me charged with a disciplinary report for inciting Florida prisoners to riot, in retaliation for me writing an article explaining the strikes purpose and the prisoners’ need of public support that was published online.[8] After a prompt kangaroo hearing and conviction of the infraction I was put in an unheated cell with a broken window as outside temperatures dipped into the 20s, and guards kept exhaust fans on 24/7, sucking the freezing air into the cell.[9]

Yet another call went out, initiated by NABPP’s comrade Malik for a renewed round of strikes across the U.S. to begin on Juneteenth (June 19, 2018). As I and several dozen prisoners at Florida’s Santa Rosa prison where I was then confined prepared a commissary boycott for this strike, and undertook to build unity among the prisoners there in solitary (to counter the culture of guard-manipulated violence between them,) I was abruptly interstate transferred back to my home state of Virginia and promptly assigned to a permanent solitary confinement status called Intensive Management.

The struggle continues

But the struggle doesn’t end there. A broad call has gone out for a sustained prison strike from August 21-September 9, 2018, for prisoners across the U.S. Participants are called on to participate in any, several, or all of the following manners:

- Work strikes: prisoners will not report to assigned jobs. Each place of detention will determine how long its strike will last. Some of these strikes may translate into a local list of demands designed to improve conditions and reduce harm within the prison.

- Sit-ins: In certain prisons, people will engage in peaceful sit-in protests.

- Boycotts: All spending should be halted. People on the inside will inform you if they are participating in this boycott.

- Hunger strikes: People shall refuse to eat.

The strike will raise the following ten general demands:

- Immediate improvements to the conditions of prisons and prison policies that recognize the humanity of imprisoned people.

- An immediate end to prison slavery. All persons imprisoned in any place of detention under United States jurisdiction must be paid the prevailing wage in their state or territory for their labor.

- The Prison Litigation Reform Act must be rescinded, allowing imprisoned humans a proper channel to address grievances and violations of their rights.

- The Truth in Sentencing Act and Sentencing Reform Act must be rescinded so that imprisoned humans have a possibility of rehabilitation and parole. No humans shall be sentenced to Death by Incarceration or serve any sentence without the possibility of parole.

- An immediate end to the racist overcharging, over-sentencing, and parole denials of Black and Brown people. Black people shall no longer be denied parole because the victim of the crime was white, which is a particular problem in southern states.

- An immediate end to racist gang enhancement laws targeting Black and Brown people.

- No imprisoned person shall be denied access to rehabilitative programs at their place of detention because of their label as a violent offender.

- State prisons must be funded specifically to offer more rehabilitative services.

- Pell grants must be reinstated in all U.S. states and territories.

- The voting rights of all confined citizens serving prison sentences, pretrial detainees, and so-called “ex-felons” must be counted. Representation is demanded. All voices count!

Conclusion

Slavery and oppressive “containment” of the marginalized and poor never ended in Amerika. The 13th Amendment was passed as a compromise to previous slave owners whereby they could continue to exploit the labor of disempowered people, but now free of the burden of paying for their upkeep. This was done at taxpayers’ expense.

This oppressive dynamic must continue to be resisted, as must the inhumane and dehumanizing conditions that attend imprisonment in Amerika. It was only by resistance that the slaves of the old antebellum slave system effectively countered the lies, and logic of the ruling powers of that system erected by them to justify their institutions of slavery. It was only by unifying in that resistance and sabotage and ultimately fighting for their freedom, with the support of outside allies and comrades, that the slaves of the old South destroyed the system as it was.

But it was only reformed into the system of penal slavery that it is now. So we still have much work to do until slavery in Amerika is abolished once and for all.

Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win!

All Power to the People!

Write to:

Kevin Johnson, #1007485

Sussex 1 State Prison

24414 Musselwhite Drive

Waverly, VA 23891

Notes

[1] Quoted in Stephen Whitman, “The Marion Penitentiary—It Should be Opened-Up Not Locked Down,” Southern Illinoisan, August 7, 1988, p. 25.

[2] Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987), basically established that if prisoner officials can invent a rational sounding justification for violating a prisoner’s established constitutional rights the courts will allow them to act illegally.

[3] Congress enacted PLRA in response to a significant increase in prisoner litigation in the federal courts; the PLRA was designed to decrease the incidence of litigation within the court system.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prison_Litigation_Reform_Act

[4] See, In re Medley, 134 U.S. 160 (1890).

[5] “California Solitary Success,” By Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, Socialist Viewpoint, Vol. 15, No. 6, http://www.socialistviewpoint.org/novdec_15/novdec_15_33.html

[6] Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, “Black Cats Bond: The Industrial Workers of the World and the New Afrikan Black Panther Party-Prison Chapter.” http://rashidmod.com/?p=1251

[7] See, Article 4 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.”

[8] Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, “Florida Prisoners Are Laying it Down.” (2018) http://rashidmod.com/?p=2498

[9] “How to Organize A Prison Strike,” Pacific Standard (May 7, 2018) https://psmag.com/social-justice/how-to-organize-a-prison-strike

Leave a Reply